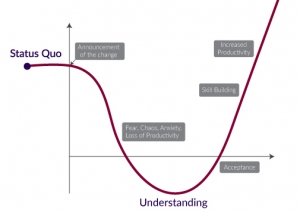

If you are in change management, you have likely seen representations of a “change curve,” depicted differently and called by many different names. The graphic below compiles the thinking of a number of change process models, from Elizabeth Kuebler-Ross change curve to Kurt Lewin to Virginia Satir among many others.

The content should be recognizable primarily because it describes the all-too-familiar process an individual or an organization goes through once an intended change is suspected or announced.

–

–

My purpose in depicting this model is to emphasize the critical nature of researching and articulating the complete business case for the organizational change at hand as the very first step in implementing a change initiative (hence the red arrow). This is a seminal moment in the project. The change has been “announced”—formally, via its inclusion in a business document, or informally via a grapevine.

At this point, those involved in managing the change have a significant opportunity to positively impact the implementation of the change by spelling out the complete case for change to all those who will be impacted, as well as to those who work with the impacted groups, and by setting the standard for transparency.

Additionally, this documented information will form the core of all future communication and messaging that comes from “change central.”

What do we mean when we say “the complete case for change”? APMG talks about The Five Case Model, a framework for proactive thinking about a business change that is a best practice of the United Kingdom’s government organizations.

The Five Cases in this model are:

- Strategic Case—how the intended change fits with the strategic objectives of the organization

- Economic Case—how the intended change will provide optimal value to the organization

- Commercial Case—how the intended change will be procured so that it is commercially viable in the marketplace

- Financial Case—how the intended change is able to be afforded by the organization

- Management Case—what will be the capital (think human capital) requirements from all involved parties to ensure success

Although this five case model is used to evaluate potential capital projects prior to making commitments, it offers a rubric against which to define the full set of “Why are we doing this?”

Exploring and articulating the business case for change requires hard work and considerable determination on the part of change management practitioners. Information coming from senior management or the program leader may be vague, incomplete, or even premature.

Practitioners can prove their value to senior leadership by defining the business case (from big picture to specifics) found in relevant business documents, and shaping it into a well-articulated Business Case for Change that incorporates the five cases mentioned earlier.

The documentation to seek out includes the latest Annual Report, the Project Charter, relevant information from Senior Executives, Board Presentations, Cost-Benefit Analyses and, of course, relevant information from the Internet.

While it may not alleviate the anxiety, fear, and distraction completely, a well-presented business case for change will provide an indication that management will be straightforward about the change. It should provide impacted groups with a clear description of what can happen to the organization if the change is not made. Having taken this first step, the steps that follow, while never easy, are facilitated through transparency and logic.

How do you articulate the business case for change? Share your thoughts on the Change Management Review Change Management Review Facebook page, or leave a comment below.